Some years back I went to see a play – Seven Acts of Mercy – at the RSC based around a painting by Caravaggio, and telling some of his life story. Some of you may have been too. It sparked off my interest in Caravaggio, who led (it has to be said) a colourful life. Passionate, at times violent, emotional and hugely talented, his pictures of scenes from the Bible and classical tales are typically realist, with people you can imagine meeting on the street –though some of them you might not want to come face to face with! His style reflects his life in many ways.

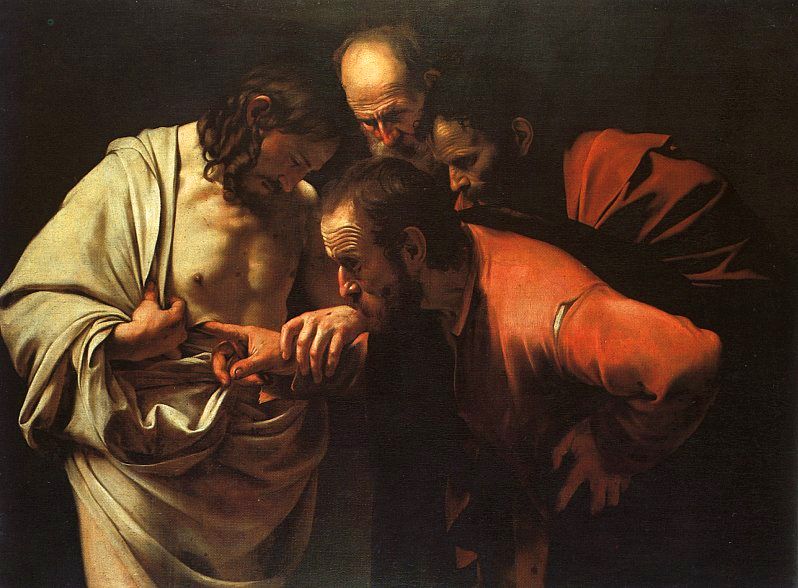

What you’re looking at here is another of his paintings – the Incredulity of Thomas. Typical of the realism of Caravaggio, we can see Thomas literally poking his finger into the side wound of Jesus, peering closely and intently at it. It is almost graphic. This is Jesus with a hole in his side. Not a holy, untouchable, ethereal figure but a real man, prod-able, human, someone you can imagine being in front of you.

With Caravaggio’s mastery of light and contrast he draws us into the action, almost as though we were there.

We can see Thomas’ face clearly. He’s having a good look, examining this wound in great detail. Look at the lines on his forehead as he concentrates on what he’s doing. Peter, the older disciple, and John are there too – having a good look as well, checking out Jesus.

It’s an image of that story in John 20. Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.

For Thomas, the presence of those wounds convinced him that this really was Jesus – alive and present yet still bearing the marks of the crucifixion a week or so ago.

Even after the resurrection, those wounds are clearly – and for Caravaggio graphically – present.

The risen Christ doesn’t inhabit a body unmarked by his torture, the pain airbrushed out. There are no golden haloes to show us how holy these men are. Jesus’ outfit is a little less than Persil white – the meeting a week after the resurrection is all about the real, human, fleshy Jesus.

And this is just what Thomas needs. He doesn’t want Jesus with a halo, he doesn’t ask to see him walk through locked doors as he had before, he doesn’t ask for another water into wine or loaves and fish moment. He asks to see those wounds, to touch them, even to ‘thrust his finger in’. He’s asking for a Caravaggio moment. He wants evidence of a broken Jesus.

Because Thomas too has been broken. He’s been through the pain and trauma of the past week, and has lost all hope. So I don’t think he’s just looking for proof. He’s looking for meaning, for an understanding of what this was all about and what happens next.

Moving into another three weeks of lockdown, I too want to know a broken God, a wounded Christ. An ethereal Christ, all pain and suffering wiped away, is no use to me in a pandemic.

Significantly, each time Jesus meets his disciples, he says the same thing. “Peace be with you”. A blessing and a promise for a new life, for wholeness.

To the wounded disciples, he says ‘Peace be with you’. To the damaged and scared parts of us, he says the same. ‘Peace be with you’.

But those would be empty words coming from a God who didn’t know quite what it was like. It would be a hollow promise of healing if Jesus didn’t know what brokenness was like.

Thomas needs to know that the risen Christ understands what it is to have a broken heart. And that the promise of peace and new life comes from a place of brokenness. The resurrection doesn’t erase those wounds, but it takes away their power and sets us free.

And for Thomas, that encounter with the wounded, risen Christ leads to the first full confession of Christ we hear. My Lord and my God.

Thomas is the first person to recognise and proclaim that Jesus is God. From unbelief to belief and a declaration that goes beyond what the other disciples have understood.

May Christ, wounded healer and risen God, meet us where we need him this week.

Sermon for Zoom Church, 19th April 2020